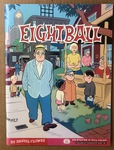

From the view here at Copacetic, it appears that Monica has received the highest profile debut of any book in Fantagraphics history – talk about buzz! When was the last time that a graphic novel made the cover / lead review of the New York Times Book Review? (those with access can read it here) Then there's the Washington Post (ditto, about access) Then there's the pieces in the LA Times, The New Yorker, Vanity Fair, and a pair of reviews in The Guardian (first | second), and that's just for starters.

In typical Clowesian fashion, Monica follows the titular character through one rabbit hole after another, as she searches for the meaning of her life – which is shown to be very much connected to the story of her mother, Penny – leading to many unexpected (and disorienting) twists and turns. This works to slowly but surely guide the reader behind Monica's eyes and into her head space. Once there, what emerges is more than just the story of one person. It is also a bleak, damning portrait of an era which neatly overlaps with the lifetime of one Daniel Clowes. Starting out on the cultural frontier that emerged in the fraught cultural ferment of the 1960s, and largely set in the west of the USA, the characters and events that constitute this portrait become gradually subsumed into the dominant cultural matrix of late-capitalism, devolving into a surreal atavistic tribalism that is grounded in illusion, leads to delusion and overwhelms any and all aspirations for meaning and individual redemption. Given the acclaim that it has received, it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that Monica has effectively embodied an integral facet of our current zeitgeist. Bummer.

And, then here's a Copacetic Exclusive: John W. Fail's insightful review of Monica!

Daniel Clowes has been with me for my entire adult life and a few years before it, and he's someone whose work I always embrace. He works slowly in his post-Eightball 'late period', but I have enough faith in him that whenever he drops a new book I don't hesitate to order it, and I'm never disappointed, though Patience and Wilson were probably second-tier work. I think because of that I had fairly low expectations for Monica, though that's the wrong term to use because from the first panel I felt a rush of pleasure at the familiarity with the man's style; I'm never disappointed, and David Boring is really his only work that I didn't care for (and perhaps if I read it again today I would feel differently). I can't exactly say he's an influence on me since I've never really tried to create anything that is inspired by him or even in the format where it could be, but there's something there in his work that's always felt like it was winking at me, like it was made specifically to speak to me, which is not something I feel much from art these days, regardless of how otherwise enjoyable the work might be. That Clowes's later work has 'matured' –– that he has seemed to make peace with the alienation and contempt that saturated his early material, without compromising his empathetic eye for the biggest freaks and outcasts of this world –– is something I appreciate more with each passing year, whenever I revisit his work. That celebration of miscreants is something that the film Funny Pages really captured, even though I don't believe that Clowes had anything to do with it –– it could well have been an adaptation of his work. Anyway, Monica is an absolute masterpiece, a total work of genius that completely blew me away, and I think justifies all of the hyperbole I'm going to indulge in. The structure is similar to how he's spent the last 2 decades exploring the conventions of Silver Age comics, with Wilson and Ice Haven indulging in different styles from section-to-section, though as the book goes along this starts to melt away and become intentionally blurry. Monica I believe is the most autobiographical work by him, even more so than when he appeared directly in some Eightball stories as himself. Here, he makes a late appearance as a surrogate character 'Stan', who has a strangely ghost-like parallel presence in the narrative, and like everything else in Monica, it never clicks together or creates a full circle of closure. The central narrative of the Monica character is so sweeping that it's beautiful, and hit me really emotionally just in the way it presents a complete, full human life in episodes –– it reminded me a little bit of the video game 'Roy' inside of Rick and Morty, where you play the complete life of an average, mundane person. Which is not to say that Monica's life is mundane, but it's also not sensational, and it's mostly built around isolation, the necessity of building one's identity on their own, and ultimately accepting and embracing the peace of older age. This is not at all straight-forward; Monica disappears for parts of the story in order to explore other conventions of comics (the horror story, the detective story) but it's all just enough there to hold together, and upon finishing it, after basking in the glow of such an accomplishment, I immediately wanted to re-read it to see what I missed, to approach from another angle. Yes, it's beautiful; some of the woodsy and foresty pages, as well as its cover and more panoramic pages, are among Clowes most hauntingly and affecting images ever, and the colours are carefully done throughout to work almost like filters on a film. Yes, it's funny, of course. It recalls many motifs and even some direct references to his earlier work, and it also is weird, with the cult story just as creepy a mood piece as Like A Velvet Glove. Krug, the cranky artist who is a minor character in the 'Pretty Penny' and reappears as an old man is the perfect, quintessential Clowes character, who could have walked straight out of a 1991 issue of Eightball, except now Clowes has figured out how to employ these figures into a larger, meaningful narrative. There are mysteries dangled throughout this that resolve into nothing (as Monica's quest to figure out her parents ultimately is resolved in the most dull of manners) and others that are huge and ambiguous; it's got some real Lodge 49 vibes there, and every bit as weird and funny as that show. But there's also a gravitas that I don't think that has been so prevalent in any of his other work, even that which has explored ageing and death before, and there was just so much here to relate to that I was really affected. David Sandlin's Belfaust, which I'm only a few issues into (and already missed my chance to snag #5, so I probably have to start hunting that down), has a similar (-ly supernatural) tale of a child's parents in the late 1960s, though with a very different context; there's something about the comics medium that makes these types of stories really resonate and not sink into navel-gazing indulgence. I avoided press about Monica but a quick glance shows that this has been received rapturously, which is good; it's deserving, but I hope that it doesn't turn into a mediocre film like Wilson (and Art School Confidential).