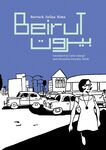

Originally published in Holland in 1968 Iris is very much a "sixties" book: psychedelic art; wild colors; sexy action; casual drug use; youthful struggles against an oppressive authority; and more.

The core of the work is located in its all-consuming focus on fame and stardom and its depiction of "stars" as being the center around which society is organized – and therefore the source of power – and of being manufactured in an almost industrial fashion by a veiled corporation (which the story implies to be one among several) led by a somewhat degenerate, Pygmalionesque dictator. In this, it overlaps in its concerns with the film Performance – which was also produced in 1968 (but not released until 1970) – in which organized crime, corporations and pop stardom are shown as being stucturally and functionally similar, overlapping layers of the socioeconomic framework. While surely influenced by Guy Peellaert's work on Jodelle and elswhere, tropes developed and employed by Tjong-Khing here in the pages of Iris also appear to prefigure some of those prevalent in the Metal Hurlant era.

And, of course, there is its highly gendered accounting of power, with its nexus shown as located in the feminine – and, specifically, in Iris herself – while its control is firmly held within the masculine. Intriguingly, these gender power relations do not wholly transcribe to biological gender. Iris's love interest is the flamboyant and somewhat feminine Michael, while there is an army of masculine women who serve "MG", the corporate overlord of the star-making factory. Additionally, there are multiple instances of cross-gender disguising and dressing which serve to accentuate the socially constructed aspects of gender. So, suffice it to say that there is plenty of food for thought regarding gender constructs and power relations. As a side note, all of this could be seen as, in part, a sort of inside-out view of Andy Warhol's "Factory" which was well underway by 1968.

This well produced 136 page (very) full color, 8 1/2" x 11" softcover marks the first publication of Iris in English, well over fifty years after its initial publication. So, a watershed moment for the Anglophone appreciation of Dutch comics.

The graphic novel itself takes up 90 pages with the rest devoted to a heavily illustrated essay by the book's colorist, Rudy Vrooman (who did a fantastic job, by the way) charting the the back story of the work and its creators as well as providing ample historical and cultural context, including the rise of Pop Art and Camp, along with Iris's precursors, Jean-Claude Forest's Barbarella and Guy Peellaert's Jodelle and Pravda.

Not to be missed!

Here's the Fanta Hype-up in full:

Available for the first time in English, this first-ever Dutch graphic novel is a tour-de-force in all its 1960s psychedelic, pop art, and playfully erotic glory.The characters' emotions drive the anti-capitalist, dystopian narrative in Iris: A Novel for Viewers, the earliest graphic novel produced in the Netherlands (Is that actually true? – ed.) . A young woman, Iris, has her heart set on a singing career, and, despite her boyfriend Mark's warnings, is seduced by the capitalist producer, "dream lover M.G." He molds her into a megastar, which leaves Mark peddling her merch: a life-sized Iris (sex) doll. Attempts to rescue Iris come to nothing; all they accomplish is allowing the dream lover to go on playing his games.

Thé Tjong-Khing's Iris marks the peak of his career as a comics artist. He and scriptwriter Lo Hartog van Banda wanted to reach the socially motivated young people of the late 1960s, who were growing up with comics and television. Khing's style here, drawn with virtuoso élan, shows an affinity with his contemporaries, such as Guy Peellaert, and Iris herself is reminiscent of Barbarella. This edition includes an afterword by graphic designer and colorist Rudy Vrooman, which provides fascinating context about the historical and artistic significance of the work and its restoration process.

Thé Tjong-Khing (b.1933) studied for three years at art school in Bandung, Indonesia. In 1956, he came to the Netherlands, where he worked at the studio of the most celebrated Dutch cartoonist, Marten Toonder. Until the end of the 1960s, he mainly drew comics like the Arman & Ilva series; Iris (1968) is his zenith as a comics artist. Then followed a rich career as a children’s book illustrator. Tjong-Khing has received many prizes for his work, including the Max Velthuijs Prize for his children’s books.

Comics scripter Lo Hartog van Banda (1916–2006) worked for Toonder Studios and wrote stories for the Lucky Luke series.

Laura Watkinson is an award-winning literary translator with a particular interest in the unusual and the mysterious. Laura has worked in England, Scotland, Germany, and Italy, and she now lives in a tall, thin house on a canal in Amsterdam with her husband, their cat, and lots of shelves of great graphic novels.